Forever chemicals in your medicine cabinet: How common drugs are poisoning the water supply

By willowt // 2025-03-14

Tweet

Share

Copy

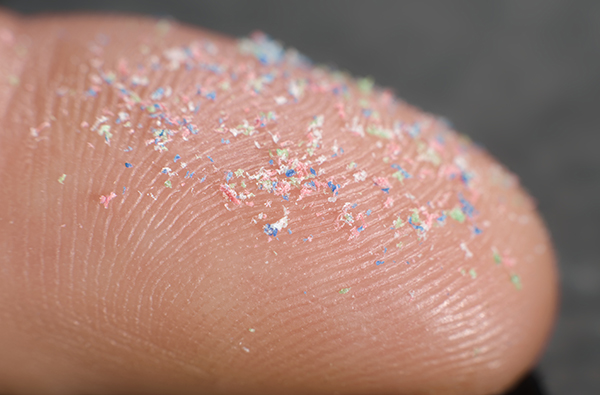

- New research reveals that common medications like Prozac, Flonase, Januvia and Celebrex are a significant source of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), or "forever chemicals," entering water supplies through human excretion and inadequate wastewater treatment.

- Wastewater treatment plants fail to remove PFAS from fluorinated pharmaceuticals, contaminating drinking water supplies for approximately 23 million Americans, with 50% of drinking water utilities located downstream of wastewater outflow plants.

- PFAS, linked to cancer, liver damage, immune suppression and developmental issues, persist in the environment. Despite EPA regulations targeting specific PFAS compounds, fluorinated pharmaceuticals account for the majority of PFAS in wastewater, exposing a regulatory gap.

- To reduce exposure, individuals can invest in reverse osmosis water filtration systems, choose spring water from trusted sources and minimize consumption of processed foods made with contaminated tap water.

- The study underscores the need for stricter PFAS regulations, improved wastewater treatment technologies and greater transparency about chemicals in medications to address this public health and environmental crisis.

The hidden pathway: From pills to tap water

PFAS are a class of synthetic chemicals known for their resistance to breaking down in the environment. Historically, they’ve been used in everything from nonstick cookware to firefighting foam, earning them the nickname "forever chemicals." But this new research reveals a lesser-known source: fluorinated pharmaceuticals. When people take medications like Januvia (a diabetes drug), Celebrex (an arthritis medication), Selzentry (an HIV drug), or Tambocor (an arrhythmia medication), their bodies excrete traces of these drugs and their metabolites. These compounds, which contain carbon-fluorine bonds — a hallmark of PFAS — enter wastewater treatment plants. Unfortunately, conventional treatment methods are ill-equipped to break down these persistent chemicals. “This pharmaceutical material doesn’t get treated in the wastewater treatment plant, and it doesn’t break down,” said Bridger Ruyle, a researcher at New York University and co-author of the study. “And we know these chemicals can be re-entering drinking water supplies.” The study estimates that this contamination affects the water supply of approximately 23 million Americans. With about 50% of drinking water utilities located downstream of wastewater outflow plants, the problem is widespread and deeply entrenched.A legacy of chemical negligence

The issue of PFAS contamination is not new. Since the 1940s, these chemicals have been widely used in industrial and consumer products, leading to widespread environmental contamination. By the early 2000s, studies began linking PFAS exposure to serious health issues, including cancer, liver damage, immune system suppression and developmental problems in children. In April 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) took a significant step by setting limits on six PFAS compounds in drinking water, including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). However, the new research reveals that these regulated compounds make up only a small fraction—7% to 8%—of the total PFAS entering and exiting wastewater treatment plants. The majority of PFAS in wastewater, the study found, come from fluorinated pharmaceuticals. This underscores a critical gap in current regulations, which focus on individual chemicals rather than the broader class of PFAS.What can you do to protect yourself?

While systemic change is needed to address this crisis, there are steps individuals can take to reduce their exposure to PFAS in drinking water. Invest in a Reverse Osmosis System: Basic water filters are ineffective against PFAS. A reverse osmosis (RO) system, while more expensive, is one of the most reliable ways to remove these chemicals from your water. Brands like Aquatru are highly recommended for their effectiveness. Choose Spring Water from Trusted Sources: If an RO system isn’t feasible, opt for spring water from reputable brands. Be sure to research the source and purification methods to ensure quality. Be Mindful of Processed Foods: Even organic products can contain contaminated water. Canned soups, jarred foods and other processed items often use tap water as an ingredient. Preparing meals at home with purified water can help minimize exposure.A call for action

The findings of this study are a wake-up call. They highlight the urgent need for stricter regulations on PFAS, improved wastewater treatment technologies and greater transparency about the chemicals in our medications. As Ruyle emphasized, “This study emphasizes the presence of organofluorine pharmaceutical waste in the environment and highlights the urgent need to understand what the health risks to these compounds are.” For now, the burden of protection falls largely on individuals. But as awareness grows, so too must the demand for systemic change. The health of our ecosystems and future generations depends on it. Sources include: NaturalHealth365.com TheNewLede.org PNAS.orgTweet

Share

Copy

Tagged Under:

Big Pharma research poison water supply ecology Dangerous Medicine water filters clean water Censored Science PFAS ecosystem disease causes environ badhealth badmedicine badpollution dangerous chemcials forever chemicals public health crisis

You Might Also Like

FLORIDA AHCA REPORT: Illegals cost state $659.9 million in uncompensated health care

By Laura Harris // Share

USDA continues MASS CULLING of poultry to address bird flu despite criticism

By Ava Grace // Share

MICROPLASTICS in wastewater fuel antibiotic resistance, study warns

By Ava Grace // Share

Autism and pregnancy: What science says about risk factors

By Olivia Cook // Share

Recent News

Preparing young children for survival situations: A guide for parents

By zoeysky // Share

U.S. moves to block Chinese control of Panama Canal, citing national security threat

By isabelle // Share

CRISPR revives dire wolves, igniting de-extinction debate

By willowt // Share